Two years after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, doing away with a half-century of precedent, activists worried that other high court decisions could be in jeopardy are taking their concerns to the polls. California, Colorado and Hawaii will soon allow their residents to vote on ballot measures that would remove language from their state constitutions prohibiting same-sex marriage.

The landmark 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges ruling, guaranteeing same-sex couples across the country the right to marry, makes these state bans unenforceable. However, these ballot measures seek to proactively protect these marriage rights should Obergefell ever be overturned.

Paul Smith, a Georgetown law professor who argued the landmark 2003 Supreme Court case Lawrence v. Texas, which struck down the country’s remaining anti-sodomy laws, said the high court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, which struck down the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade abortion ruling, should serve as a cautionary tale.

“We’ve had the example of how Dobbs can take down a long-standing precedent. Suddenly there are these state laws that were sitting there dormant, that came springing back to life,” he said, referring to the dozens of states that now have abortion bans following the Dobbs decision. “These states don’t want their same-sex marriage bans to come springing back to life, so they’re going to do something about it, if just in case.”

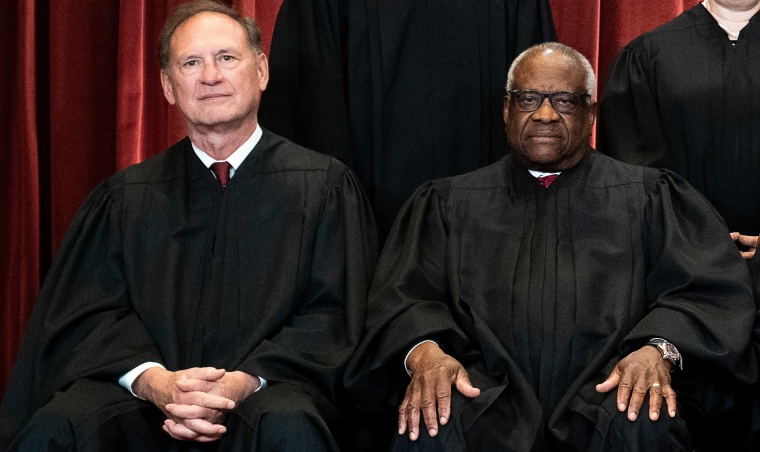

Smith validated the potential concern, pointing to Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurring opinion in the 2022 Dobbs decision.

Supreme Court Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas in Washington in 2021.Erin Schaff / Getty Images file

Supreme Court Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas in Washington in 2021.Erin Schaff / Getty Images file“In future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell. Because any substantive due process decision is ‘demonstrably erroneous,’ we have a duty to ‘correct the error’ established in those precedents.” Thomas wrote. (Griswold v. Connecticut is a 1965 high court ruling that established the right of married couples to use contraception.)

Earlier this year, Justice Samuel Alito renewed his criticism of the Obergefell ruling in declining to weigh in on a lower court case involving a dispute over dismissed jurors who had expressed religious concerns over same-sex relationships. Alito wrote that the case “exemplifies the danger” he sees in the 2015 decision.

“Namely, that Americans who do not hide their adherence to traditional religious beliefs about homosexual conduct will be ‘labeled as bigots and treated as such’ by the government,” he wrote.

The nine-member Supreme Court is the most conservative in a century, with six justices having been nominated by Republican presidents and three by Democrats. Ahead of the 2024 election, GOP senators are hopeful about the prospect of confirming even more conservative justices, as well as lower-court judges, if former President Donald Trump returns to the White House.

Mary Bonauto, one of the lawyers who argued Obergefell before the Supreme Court, said the high court is “a very unpredictable court at this point” and added that ballot measures like the ones in California, Colorado and Hawaii are a way for states to use their power.

“They have been aggressive about reversing precedents,” Bonauto said of the Supreme Court. “They have completely remade how they deal with the powers of the government.”

Bonauto, now the senior director of civil rights and legal strategies at GLBTQ Legal Advocates and Defenders, or GLAD, said that under the current circumstances, she doesn’t understand why anyone who has a chance to remove currently unenforceable language banning same-sex marriage from their state constitution “wouldn’t jump on it.”

Currently, 30 states have constitutional amendments banning same-sex marriage, with five also having statutes that prohibit such marriages, according to the Movement Advancement Project, an LGBTQ think tank. An additional five states have bans through statutes, though no constitutional amendments. In most of these cases, Smith said, the currently dormant provisions would become law again should Obergefell be overturned, just as long-dormant state abortion bans took effect after Roe v. Wade was struck down (constitutional amendments to protect or expand abortion rights will be on the ballot in 10 states next month).

Without Obergefell, there is federal legislation that would keep same-sex marriage rights mostly, but not entirely, intact: the Respect for Marriage Act. Signed into law by President Joe Biden in 2022, the bipartisan measure ensures federal protections for same-sex and interracial marriages. The law requires the federal government to recognize these marriages and guarantee them the full federal benefits of marriage, but it stops short of requiring states to issue marriage licenses contrary to state laws.

Bonauto and Smith agree it’s an important piece of legislation, but Bonauto noted there’s always a chance it could be repealed, should the balance of power shift in Congress, and Smith said the measure would leave those in conservative states vulnerable.

“Even if you can travel to New York to get married, to have suddenly in the law a provision that says you, out of all the people in our state, don’t get to pick your spouse… that would be a terrible thing to have on the books,” Smith said. “I don’t think states want to have that kind of thing — that second-class citizenship — restored, even if there is a workaround through the Respect for Marriage Act.”

Susy Bates, the campaign director of Freedom to Marry Colorado, a bipartisan organization dedicated to preserving equal marriage rights for same-sex couples, said if Obergefell were overturned and states had to rely on the Respect for Marriage Act, it would be “really murky.”

“Unless we take proactive measures, we can’t guarantee that marriage equality will be protected in the state,” she said.

It’s a personal issue for LGBTQ couples who had to navigate a time when same-sex marriage wasn’t legal or straightforward.

2 settimane fa

19

2 settimane fa

19

English (US) ·

English (US) ·